First female U.S. Senator was unabashed white supremacist

Rebecca Latimer Felton was the last slave-owning member of the U.S. Congress and outspoken advocate of lynching.

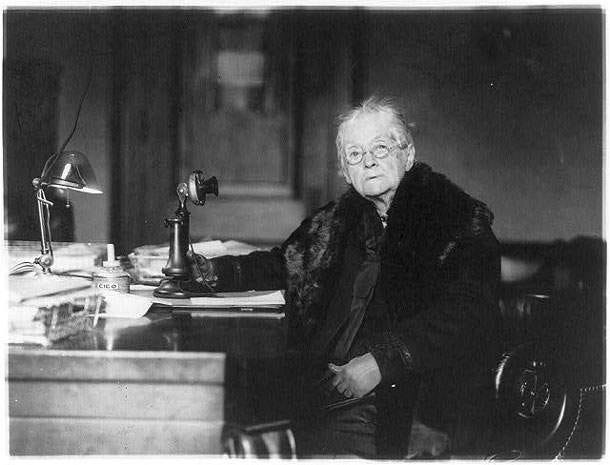

The first woman to be seated in the United States Senate, Georgia’s Rebecca Latimer Felton, was considered a pioneering Georgia suffragette, conservative writer and widely-respected social advocate when she accepted the honorary appointment on November 21, 1922.

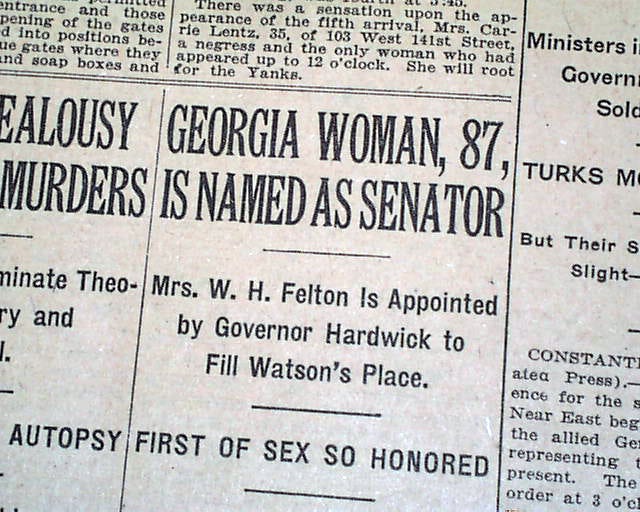

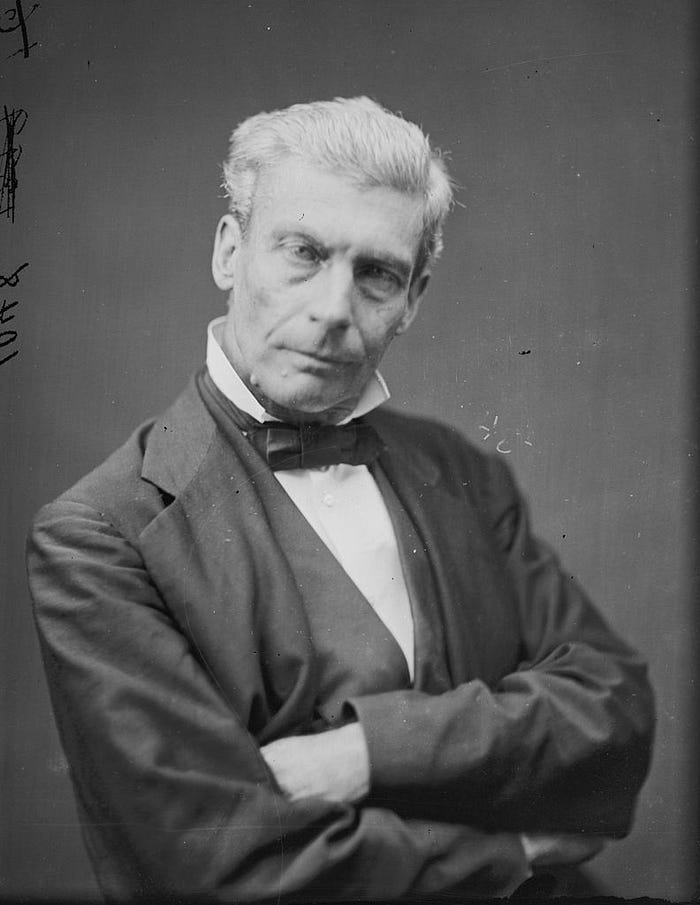

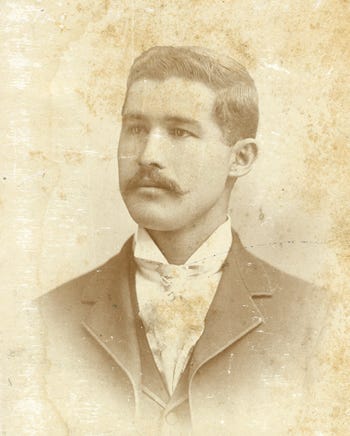

Her route to this seat was a bit unconventional. At the time, Georgia Governor Thomas Hardwick greatly opposed women’s suffrage, and accordingly the state had failed to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment giving women the vote. Then, when Senator Tom Watson died suddenly, a special election was called. Gov. Hardwick appointed the former William Harrell Felton’s wife in a ceremonial gesture to not only appease women angered by the failure of the passage of the nineteenth amendment, but to boost his own political image and fill a vacant Senate seat prior to the special election taking place. Hardwick then lost the special election race to Walter F. George, but George honored Hardwick’s appointment and swore in Felton to serve a 24-hour stretch on November 22, 1922.

“When the women of the country come in and sit with you, though there may be but very few in the next few years,” the 87-year-old Felton said of her honorary and very temporary position, “I pledge you that you will get ability, you will get integrity, purpose, you will get exalted patriotism, and you will get unstinted usefulness.”

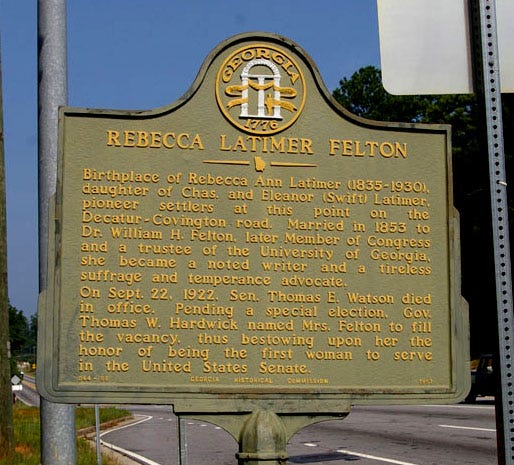

Felton for all purposes is a seemingly quintessential women’s rights advocate, worthy of accolades and honor for her work as a suffragist, a temperance, social and public education advocate and the first sitting U.S. female Senator. There is even a historical highway marker at her birthplace in DeKalb County, honoring her accomplishments. “… She became a noted writer and a tireless suffrage and temperance advocate,” reads the text in part, “… thus bestowing upon her the honor of being the first woman to serve in the United State Senate.”

But what this historical marker, as well as many historical accounts of Rebecca Latimer Felton’s colorful life fail to mention, is that she was — even for her time — a white supremacist; a malicious and ferociously outspoken racist who went so far as to actively promote the lynching of thousands of black men.

Life

Felton was born in 1835 on a 725-acre plantation in Decatur, Georgia to a wealthy slave-owning family. She lived a relatively easy life as the oldest and an admitted “daddy’s girl” until she graduated at age 17 from Madison Female School, where she learned chemistry, business and fine arts. In 1853 she married William Felton, a physician and Methodist minister, and they lived on a farm with several slaves of their own in Cartersville, where they raised a daughter and four sons. Their farm was heavily damaged during the Civil War, so afterward she taught school to help pay for repairs.

An astute businesswoman, Felton both managed her husband’s successful 1874 Independent Democrat campaign for the U.S. House of Representatives representing northern Georgia for three terms, then worked as his congressional secretary and advisor. In 1884 William was elected to the Georgia house of representatives, serving there until 1890 with his wife as his aide. In 1894 William ran unsuccessfully for the U.S. House on the Populist ticket.

Felton’s presence on her husband’s campaign trail, both as a manager and an advisor was an unusual place for a woman, and it drew heavy criticism from their opponents. She later recalled “I did not stop to think what a change this was for a young woman considered only an ornament and household mistress.”

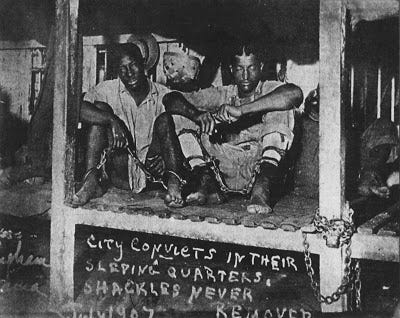

As a public figure with political experience, Felton galvanized her influential support around social interests of the time. She despised the old “Bourbon Triumvirate” government that held a stranglehold on Georgia’s U.S. Senate seats and governor’s office from 1872 to 1890. She enthusiastically supported prohibition and public education, especially vocational training for poor, white Georgia girls, and to her credit fought against the state’s barbaric convict leasing program, which made the old “triumvirate” guard wealthy by frequently working penitentiary prisoners literally to death.

Felton nurtured controversial views not just toward blacks but on the very women’s suffrage movement she held so dear. She maintained that white women should remain subservient to white men, so she wasn’t pushing for women’s equality, just voting rights — and only for white women. Like the national suffrage movement, Felton was apathetic to black women’s voting rights, and never mentioned support for them.

Also at this time Felton’s more ruthless visions of social order boiled to the surface, reflecting the extremist stances of southern white ruling classes. She defended deplorable working conditions in southern cotton mills and heavily criticized labor unions that sought to improve them. She lashed out personally at critics perceived by her as enemies.

Of course, these views as a public figure, as well as her writing for the newspaper she founded with her husband, The Cartersville Courant, made her a hero to white Georgia men and especially women.

World’s Fair

Because of her stature and influence, she was asked to help oversee Georgia’s exhibits at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The official U.S. House of Representatives history archives benignly states that “It was her participation in managing Georgia’s exhibits … that sparked her interest in national politics.”

The archive fails to admit, however, that the exhibit Felton proposed was a whitewash of the horrible realities of southern slavery, choosing to display not the evils depicted in the controversial book “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” but “the ignorant contented darky — as distinguished from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s monstrosities.” As the last former slaveholding member of the U.S. Congress, Felton wanted to exhibit what she described as the “true story of slavery,” complete with a shack and “real colored folks making mats, shuck collars, and baskets — a woman to spin and card cotton — and another to play banjo and show the actual life of [the] slave — not the Uncle Tom sort.”

Her proposition to put living black people on display to promote a positive image of southern American slavery was obviously meant to reflect her sanitized personal experiences. In context this was not that unusual for the time and especially of this exposition — one of the draws of that monumental Chicago Fair was the inclusion of “living museums” of “primitive” human beings “displayed to fairgoers as objects of anthropological inquiry.” Fair organizers imported groups of Samoans, Hawaiians, Algerians, Dahomeans and even Native American Indians especially for the purpose of showing Americans how far they had societally progressed. The “Java Village,” comprised of indigenous peoples from the villages of Sinagar and Parakan Salak was one of the most popular at the fair.

Felton even suggested for her exhibit two blacks whom she knew, “Aunt Ginny and Uncle Jack,” whom she considered “Two darkies of the old regime that don’t know a letter in the book.”

Her idea was apparently warmly received. “Everybody says it will be splendid,” she wrote, adding that she could depend on Aunt Ginny and Uncle Jack to be “sober and well-behaved.”

As evidenced by her proposal, Felton’s opposition to slavery was not motivated by the ethical quandaries of human ownership — she instead condemned white men for pursuing ownership of slaves because as such they were pursuing status, and not as focused on protecting and caring for their white women at home. Rural Georgian women were raised in a system that emphasized men’s protection of them. To Felton, white men betrayed this mission when they selflessly pursued slaves.

The Speech

Felton’s racial arrogance was fully highlighted in a jaw-dropping speech to the Georgia Agricultural Society at Tybee Island on August 11, 1897. In it, Felton conflated her racism with women’s suffrage, stating that farm wives faced many dangers but none greater than “the threat of black rapists.” She argued that the use of liquor to purchase black votes contributed to an increase in threats to southern womanhood, since blacks presumably became even more out-of-control when drunk. She also claimed that charitable donations for missionaries overseas would be better spent educating virtuous young white ladies who had been left unprotected by poor white southern men from the drunken black rapists.

She then insisted that vigilante justice, in the form of lynching, was an effective way for white men to restore that protection to their women. “When there is not enough religion in the pulpit to organize a crusade against sin; nor justice in the court house to promptly punish crime; nor manhood enough in the nation to put a sheltering arm about innocence and virtue — if it needs lynching to protect woman’s dearest possession from the ravening human beasts — then I say lynch, a thousand times a week if necessary. The poor girl would choose death in preference to such ignominy, and I say a quick rope to assaulters! The crying need of women on the farm is security.”

Furthermore, Felton challenged Southern white patriarchy in the same speech: “as long as your politicians take the colored man into their embrace on election day … so long will lynching prevail, because the cause of it will grow and increase, for ‘familiarity breeds contempt.’”

The speech was a hit. According to the Kansas City Journal, at the conclusion “the audience rose as if by a single impulse, and shouting themselves hoarse and almost delirious, refused to let the speaker go on for several minutes.”

Newspapers that published Felton’s incendiary speech escalated simmering southern racial tensions at a time when blacks were already facing their worst discrimination since the war, forcing an almost immediate rebuke by Alexander Manley, editor of the black-owned Wilmington Daily Record newspaper. His editorial “Mrs. Felton’s Speech” amplified tensions even more by not-too-subtly charging that white men wielded economic and political supremacy over black women in the segregated society of the time, and had openly preyed sexually on those women during slavery and even after the Civil War. Manley also alluded that many accusations of rape were simply cases of a black man having a consensual affair with an infatuated white woman. Reprints of this editorial by other newspapers across the South further enraged the white population up to the November 8, 1898 elections, which saw Rutherford B. Hayes elected President and federal protection for southern blacks removed.

coup d’état

Only two days after the election, and with the security of federal troops gone, thousands of Wilmington whites rioted in what became the only coup d’état in United States history, today called the Wilmington insurrection or Wilmington race riot of 1898.

The riot actually overturned the city’s government. All black politicians, and especially Manley and his brother, were given the harsh choice of leaving town or be killed. Black neighborhoods were decimated in this riot, and it is estimated that up to 100 black men, women and children were murdered — many of them bludgeoned to death and thrown into the Cape Fear River — and up to 250 wounded. Manley’s newspaper offices were destroyed by a crowd estimated at 1,500 strong.

Declared openly by the rioters as an outlaw to be killed on sight, Manley and his brother Frank got out of Wilmington and eventually made it to Washington DC then Philadelphia. As a result of the insurrection, austere restrictions were subsequently placed on black voting in North Carolina.

These deadly responses to Felton’s words did nothing to silence her, and she appeared unmoved by the reactions to them. In a response to the Wilmington massacre, she stated incorrectly that since her Tybee Island speech, rapes and lynchings had actually decreased 50 percent, but in fact Georgia lynchings were increasing, doubling between 1889 and 1899. She also continued a crusade to strip funding from black education, claiming again with no proof that in Georgia the number of crimes committed by blacks increased proportionally to the amount of money spent on black education.

“Less sympathy than a rabid dog”

Felton further cemented her shameless, vengeful racism in 1899, after a crowd of thousands of white Georgians tortured, mutilated and burned to death a black man, Sam Hose, who allegedly was paid $12 by a Baptist preacher to kill his white employer, Alfred Cranford, over a wage dispute. He was also accused of attacking Cranford’s wife, although separate investigations by Ida B. Wells and a white detective both disproved that allegation.

At a symposium hosted by the Atlanta Constitution newspaper, Felton shrugged at the brutal and senseless barbarity of the Hose lynching, claiming that the rape of “helpless white women” (even though the accusation that Hose committed rape was suspect) placed the black perpetrator “beyond the pale of human mercy.” Any “true-hearted husband or father,” she added, would also have killed “the beast” and that Sam Hose was “due less sympathy than a rabid dog,”

Sam Hose definitely received less sympathy than a rabid dog. The Atlanta Constitution reported that 2,000 white witnesses joyfully watched as he was chained to a pine tree and his ears sliced off, forcing a most likely false confession. His fingers were cut off one by one and passed among the cheering crowd as souvenirs. He was then sliced, mutilated and even castrated before he was covered in kerosene and burned alive. After death his blackened heart was also sliced up and passed around, as was the pine tree he was chained to.

Other women on that symposium disagreed with Felton’s insistence on mob rule. Journalist Mary E. Bryan argued that “to inflict torture and cruel death as a penalty for brutish crimes is to imitate the negro in barbarism and to develop the instinct of savagery that underlies all our civilization.” Annie Johnson, President of the Georgia Federation of Clubs, agreed, saying “Let the laws be strong and vigorously, but justly, enforced, and fear will go far to prevent crime.”

The next day Lige Strickland, the black preacher and married father of five children who allegedly paid Hose to kill Cranford, was found hanging from a persimmon tree. Like Hose, his ears and left little finger were gone. Pinned to his chest was a scrap of paper that intentionally or not echoed the words and sentiment of Rebecca Felton: “We must protect our ladies.”

The reverse said “Beware all darkies. You will be treated the same way.”

In 1900 Felton officially joined the Women’s Suffrage Movement, where she continued to advocate for white women’s rights, including not just the right to vote but for free public education for women and their admittance into public universities. Despite her efforts, suffrage was an uphill battle for decades in Georgia — in 1919 it was the first state to reject the Nineteenth Amendment, and was almost the only state in the Union to not allow women to vote in the 1920 presidential election. Georgia did not pass a voting rights act for women until 1922.

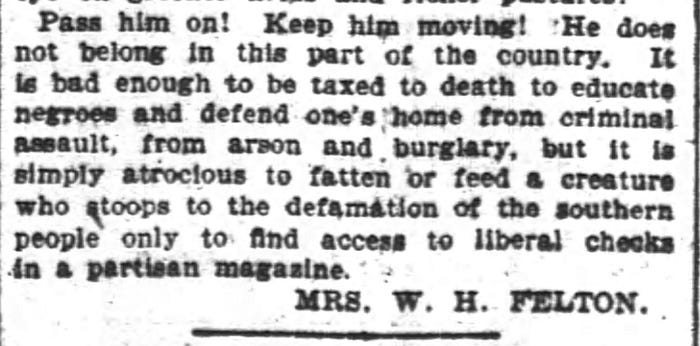

On August 3, 1902 Felton proved her white supremacy had softened little when she defended her repugnant position on the Hose lynching with a vitriolic response in the Atlanta Constitution to an essay appearing in The Atlantic Monthly, written by an Emory Professor named Andrew Sledd. In the Atlantic, Sledd (a “sniveling inkslinger” according to Felton) was harsh on white Georgian men, their treatments of blacks and especially their lynchings.

Felton went ballistic at Sledd’s singling out Georgia lynch mobs while appearing to ignore lynchings in other states. She especially attacked his position that what happened to Sam Hose was “the purest savagery,” getting her facts wrong while defending the inhuman butchery of Hose’s lynch mob:

This white man [Sledd] has not a single word to say of the fiendish murder of a father and husband, of the outrage inflicted on the agonized wife and mother, who was blood-covered beside the body of her dead husband, or of the little girls who witnessed who witnessed the horrible sights, and his logic is only here applied to condemn the white men who put the beast to death! … Every man in Georgia should read this outrageous indictment of southern manhood and dismiss the writer of it!

Because of the ensuing avalanche of bad public relations generated toward Sledd and Emory across the South by Felton’s letter, Sledd tendered a letter of resignation, stating that the opinions expressed in the Atlantic Monthly article were his own, and based his resignation on his desire to spare Emory any embarrassment and suffering related to it.

No apologies

In her 1911 book “My Memoirs of Georgia Politics” Felton never apologized for any pain or suffering she caused, but did try to deflect her earlier attitudes, particularly about slavery:

I am convinced the time had come in the providence of God, to give every human creature its title to freedom, and negro slavery was doomed and disappeared! It was not the South alone that had sinned on this line for the North had brought these slaves over here and made big money with the slave trade, and sold them Southward for strictly profit and gain, but the slaves were located in the South and this theater of current events located in the South made the South the battlefield and the sufferer from the devastating inrush of armies.

After her single day in the U.S. Senate, Felton returned to Cartersville, Georgia, and continued to lecture and write on social reforms. Revered in her later years as the “grand old woman of Georgia,” and with her racism muted, she made a brief appearance in Atlanta in 1927 when Georgia added a statue of Alexander Stephens to National Statuary Hall.

Rebecca Latimer Felton died in Atlanta on January 24, 1930 at age 95. She is to this day still the only woman from Georgia to serve in the U.S. Senate.

Read more at www.dalebrumfield.net.